Narcotic Struggles: Hash Rebels and the Fight for Alternative Spaces in West Berlin

In the mid-1960s, West Berlin saw the first glimpses of an emerging public drug scene, which would become a widespread phenomenon in the decades to come. With the rise of youth protest and an emerging “counterculture,” substances like cannabis, opioids, LSD, and heroin started to spread through the city’s parks and squares, as well as into clubs, bars, and cafés.

In addition to these substances, use of alcohol and an increasing variety of pills such as Captagon and barbiturates was already widespread among the city’s population. By the late 1960s, the public consumption of such illegalized substances, especially cannabis, but also “Berliner Tinke” a mixture of morphine base and acetic acid soon largely replaced by heroin, became impossible to ignore. Among other reasons, this phenomenon took a distinctive shape in Berlin because it was deliberately exercised in public spaces and openly practiced in clubs and bars. For some, the collective consumption of cannabis in particular even became a form of radical political activism.

The Central Council of Roaming Hash Rebels

Born out of the growing hippie movement of West Berlin, the “Zentralrat der umherschweifenden Haschrebellen“ (Central Council of Roaming Hash Rebels) was formed in the spring of 1969, ironically taking its name from a text by Mao Zedong, “On The Ideology Of Roving Rebel Bands.” This group was comprised of young dissidents and hippies, and was almost exclusively male. Understanding themselves as radical revolutionaries, the Hash Rebels argued that intoxicating states have a mind-expanding effect and therefore have the potential to make people aware of their disenfranchisement – thus encouraging resistance and constituting the first step to a revolution.

This approach, however, was controversial within the left-wing protest movement. Some saw it as destructive or even counter-revolutionary, since drug consumption also had the potential to paralyze people’s political capacity to act, and the buying and selling of drugs by even the smallest-scale dealers perpetuated the dependency-creating market laws of capitalism. Different views on how often and how much hash smoking was allowed repeatedly erupted into serious conflicts within communes, bars, and shared flats. At times, these conflicts ended with representatives of the “hash faction” being thrown out the door.

Nevertheless, members of this faction were convinced that the interactions brought about by collective consumption of marijuana, especially in public, were linked to the possibility of anchoring revolutionary thought in a “proletarian” subculture; this would overcome the gap between the academic extra-parliamentary opposition and the actionist-anarchist commune movement. They also advocated for the use of marijuana as well as other illegalized drugs, such as opium and LSD, as a means of overcoming societal constraints and producing liberated ¬– and therefore potentially revolutionary – subjects.

Smoking for the Revolution

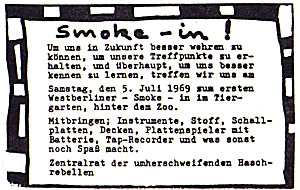

Collective consumption of illegalized substances such as marijuana as a form of political protest had already been tried out in the US, with the large “Smoke-Ins” in New York’s Washington Square Park as the most prominent model. The first such public happening was the Smoke-In in Tiergarten, the largest park in West Berlin, on the July 5, 1969. The event was widely announced by flyers such as this one:

Invitation to the first public Smoke-In in Berlins Tiergarten 1969

In the late 1960s, the idea of collective consumption of illegalized substances such as marijuana as a form of political protest had already been tried out in the US, with the large “Smoke-Ins” in New Yorks Washington Square Park being its most prominent model. The first of such public happenings was the „Smoke In“ at the large park Tiergarten on the 5th of July 1969. It was widely announced by flyers, such as this one.

UnknownTRANSLATION:

In order to be able to defend ourselves better in the future, to maintain our meeting places, and in general to get to know each other better, we will meet on Saturday, 5 July 1969 for the first West Berlin Smoke-In Im Tiergarten, behind the Zoo.

Bring along: Instruments, substance, records, blankets, record player with battery, tap recorder and whatever else is fun.

Central Council of the Roaming Hash Rebels

While being a rather small crowd of around 50 young, and predominantly male, people, the event drew considerable attention by the public and media as well as the local authorities and the police, who to everyone’s surprise did not intervene.

This short film, shot on an 8mm film, gives some impressions of this event:

A participant describes the event as follows

Our Smoke-In looked like this: everyone smoked their joint in public, of course, and everyone felt much safer than alone at home, despite constant police patrols (on horseback, with dogs and radio). Smoking together is simply more fun. You smoke the joint together with many people whom you only meet briefly and individually except at demonstrations. Collective and permanent meeting places are the starting point for the continuation of a hash campaign conducted according to Marxist-Leninist guidelines.

Interview with Ralf Reinder, in: Ralf Reinders/Ronald Fritzsch: Die Bewegung 2. Juni, Gespräche über Haschrebellen, Lorenzentführung, Knast, Berlin: ID-Archiv, 1995, p. 23, translated by Stefan Höhne.

Such gatherings soon became frequent events, drawing ever-larger crowds and gaining a widespread reputation beyond Berlin. The political message, however, soon moved into the background.

Hair and Smoke: An Early Protest against Countercultural Appropriation

Especially for some of the earliest participants of the public Smoke-Ins, these events soon lost their potentially revolutionary force. While still frequently joining these events, the Hash Rebels now looked for alternative forms of protest that were more radical. Quarrels between group members and police during demonstrations soon became a common occurrence, increasingly accompanied by acts of sabotage.

One first climax of such militant actions was the protest of the Hash Rebels against the Berlin premiere of the musical Hair at the Beautiful Balloon theater (later: Schaubühne) on October 3, 1969. For them, the musical was nothing less than a cynical and sinister form of appropriating and high-jacking hippie counterculture for capitalist gain, while at the same time, many alternative spaces in the city where frequently raided or shut down by the police.

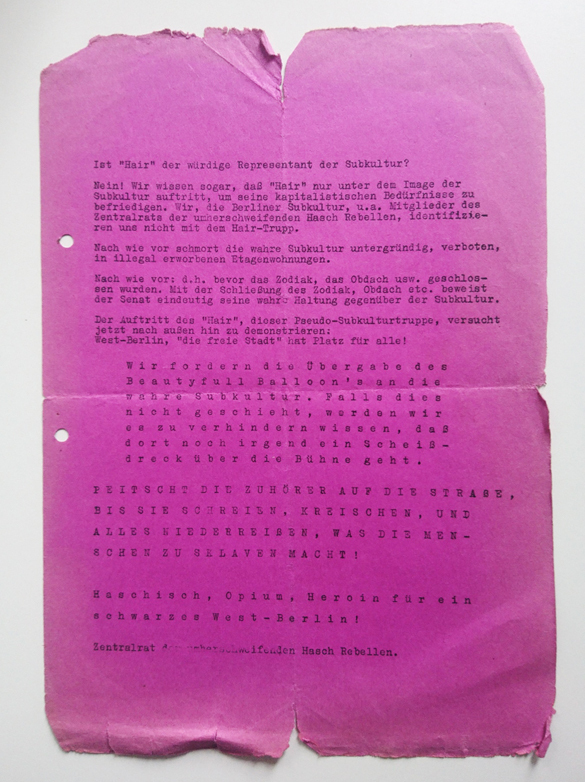

The rebels, who saw themselves as the only authentic representatives of this counterculture, distributed leaflets all around the city, calling for not only for a boycott of the show but also for militant resistance. The leaflet ended with the Rebels slogan “Hashish, Opium, Heroin – for a black West Berlin!”; with “black” referring not so much to black culture, but to the color of anarchism.

Leaflet of the West Berlin Hash Rebels 19691969

Leaflet of the the “Zentralrat der umherschweifenden Haschrebellen" (Central Council of Roaming Hash Rebels) protesting the Berlin premiere of the Musical Hair in late 1969.

Zentralrat der umherschweifenden HaschrebellenTRANSLATION:

Is 'Hair' the worthy representative of the subculture?

No! We even know that 'Hair' only appears under the image of the subculture to satisfy its capitalist needs. We, the Berlin subculture, members of the Central Council of Roaming Hash Rebels, among others, do not identify with the Hair squad.

As before, the true subculture stews underground, forbidden, in illegally acquired flats.

Now as before: that is, before the Zodiak, the shelter, etc. were closed. By closing the Zodiak, shelter, etc. the senate clearly proves its true attitude towards the subculture.

The appearance of 'Hair', this pseudo-subculture troupe, is now trying to demonstrate to the outside world:

West Berlin, 'the free city' has room for everyone!

We demand the handover of Beautyfull Balloon [sic!] to the true subculture. If this doesn't happen, we will know how to prevent any more shit from going onstage there.

WHIP THE AUDIENCE INTO THE STREETS UNTIL THEY SCREAM, SHRIEK AND TEAR DOWN EVERYTHING THAT MAKES PEOPLE SLAVES!

Hashish, opium, heroin for a black West Berlin!

Central Council of the Roaming Hash Rebels

This announcement of militant action was not an empty promise. During the evening of the premiere, the activists detonated a smoke bomb in the theater, resulting in massive police action and injury to an 80-year-old actress. The rebels, however, escaped unharmed.

This was not the only effective militant action by the activists. From December 31, 1967, to February 6, 1971, alone, there were about 70 attacks with arson, explosives, and firecrackers on US facilities in West Berlin to protest the Vietnam war, which was seen as an imperialist action against anti-capitalist resistance. In addition to the Hash Rebels, these attacks were carried out by a wide variety of small militant groups, such as the Tupamaros West-Berlin. Judicial institutions, banks, city halls, district offices and consulates as well as the press were also targets.

On May 1, 1971, during another Smoke-In organized by the Hash Rebels at the large park Hasenheide, the Yippies Westberlin were founded, inspired by a political offshoot of the hippie movement in the US. In 1972, some of its members as well many Hash Rebels joined the “Bewegung 2. Juni” (June 2 Movement, named after the date of the murder of the student Benno Ohnesorg by Berlin police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras during a demonstration in West Berlin on 2 June 1967). This marked the unofficial end of the rebels. After a series of militant actions and bombings, this radical “urban guerrilla” group came to be considered a terrorist organization by the state. Eventually going underground, the ideologies of its members ended up being very different from the politics of claiming public spaces through collective narcotic enjoyment.

Stefan Höhne