Contested Space:

Syringes in a Community Garden

by Sage Anderson

Set in the seasons leading up to 2020, this story takes place in a public community garden in Bonn, Germany, in a small lot surrounded by low-rise apartment buildings, in a quiet part of town not far from the Rhine. There was once a playground on this site, but it fell into disrepair and disuse. Increasingly overgrown with plant life – and thus shielded from street view – the abandoned playground was subsequently used primarily by people consuming drugs and alcohol. When agricultural students from the local university applied to turn the space into a community garden, the city agreed to rent it to them for a nominal fee if they would assume responsibility for its upkeep. Over the next years, the garden grew to include raised wooden beds on one side, and an open space for relaxing on the other side, with a table and a few folding chairs. While an organized group of community members tended the beds for their own private harvesting, the garden remained open for the public to enjoy: that was the idea.

Over time, members of the garden group – the author of this story among them – were confronted with conflicting interests in the space. Most problematically for the group, other people were using the open half of the garden at night and leaving behind trash and materials related to drug consumption, including used syringes. While the trash was annoying given the responsibility of garden members to care for the space, the syringes were the primary concern, especially because the area where they were left was used in the daytime by children playing in the grass. In addition to concerns about safety – as well as liability for any injuries, including to people consuming drugs – garden members were concerned about handling the needles themselves to dispose of them.

There was much discussion and some disagreement within the group on how to address this issue, highlighting tensions between the desire to cultivate a particular environment and the desire to maintain a truly public space. The group tried various strategies, ranging from more prominent signage asking people to remove their own trash, to a fake security camera reluctantly installed on a tree to present the appearance of surveillance. Additionally, a low wooden fence was added to the perimeter, and the chairs were folded up in a secluded corner every evening to discourage nighttime gatherings. The gate stayed open, however, and garden members continued to occasionally find trash and drug paraphernalia in the morning, on the ground and on the table.

This story has no satisfying resolution, much less a happy end. Garden members remained on the newly installed fence about how to best deal with the situation, and meanwhile the Covid-19 pandemic picked up speed, preventing the group from gathering. The garden grew wilder and less sociable, and the question of how best to respond to discarded needles was left unanswered, sure to come up again with the return of spring days and warm nights.

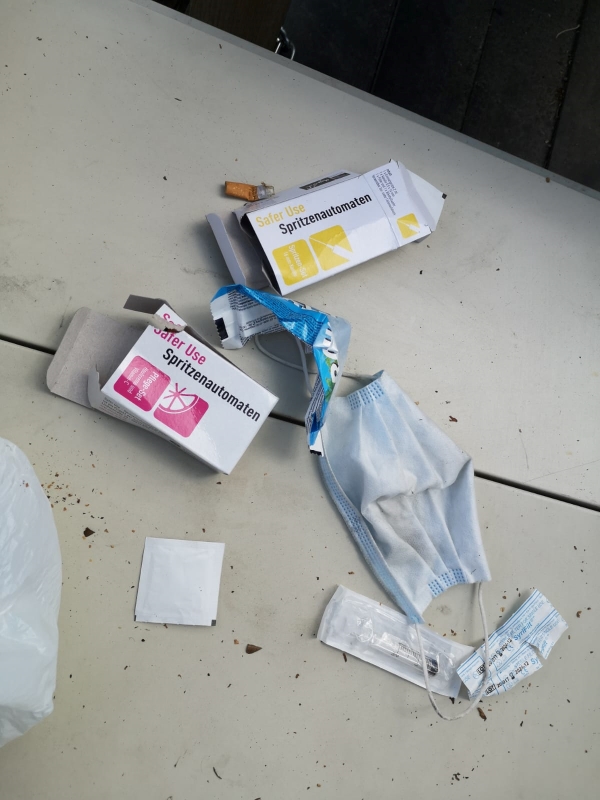

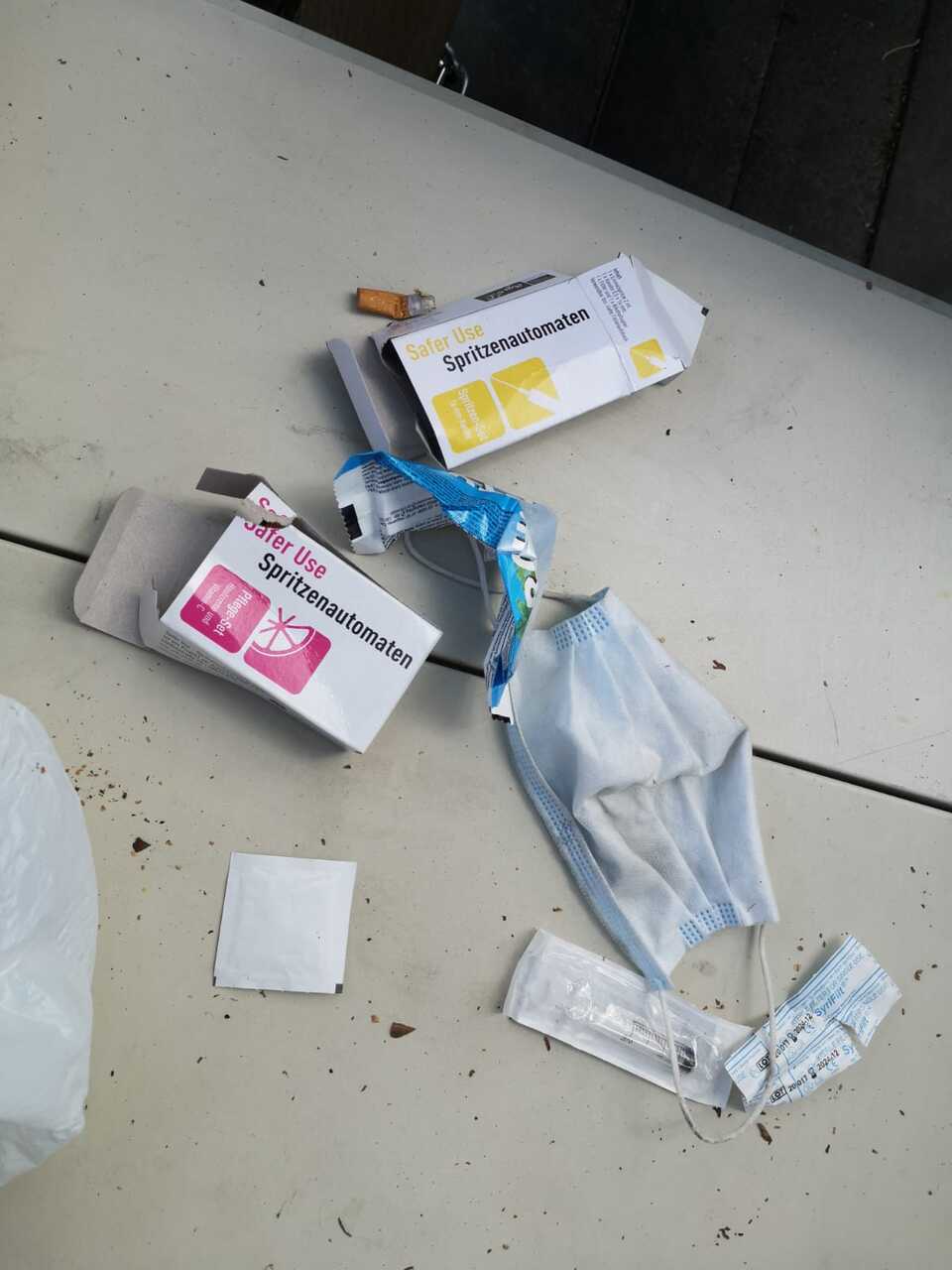

Tidy conclusion aside, the material remnants of drug consumption in this garden plot offer an opportunity for critical reflection. Many factors are at play in the assembly of items in the above image, which I will only begin to unpack here. On the table we see a plastic bag, candy bar wrapper, cigarette butt, medical mask, two boxes from the Spritzenautomat (syringe vending machine) – one Spritzen-Set (needle set), one Pflege-Set (skin care set) – part of a syringe still in its wrapper, the wrapper from another part of the syringe, and a small square package presumably containing an unused alcohol wipe. To a greater or lesser extent, each of these items is associated with potential danger to oneself or others. Plastic bags have warnings that children could suffocate. Candy bars may come with the advice to consume them as part of a balanced diet, but the very real health risks of refined sugar still attract far less societal attention than the dangers of cigarettes , heralded by glaring images and statements on the packages in which they are sold. By contrast, the neutrally packaged boxes from the Spritzenautomat materials are labeled “Safer Use”: these materials have more in common with the medical mask than the cigarette butt in this respect. As for the mask, it signals the prevailing danger of the moment when the picture was taken, namely airborne spread of the Covid-19 virus.

These objects have been left behind as trash. Their presence on the table points beyond the image to other surrounding factors, most relevantly the absence of a public trash can in the surrounding area. This is part of the reason that trash disposal is a burden for members of the garden group, and it is presumably also a factor in the decision of nighttime visitors to leave their trash behind. Also not pictured is the garden itself, and the organic materials – plants, soil – that stand in contrast to the discarded plastic and paper artifacts.

The contrast between surrounding garden and discarded objects highlights the conflict of interests that drives this story: Who is welcome to use a given public space, and for what purposes? The decision by the city to support the development of a community garden in this location can certainly be seen as a means of discouraging drug use. Where the abandoned overgrown playground once offered protective cover for an illegalized activity, the clearing of the space for sanctioned use literally brings such activities to light. The persistence of drug use in the garden at night – as evidenced by the presence of discarded paraphernalia – indicates that alternative spaces serving this purpose are not readily available. The syringe vending machine provides limited access to safe materials, but it does not address the lack of safe space for drug use. Consumption rooms do address this issue, and there is a consumption room in Bonn – albeit far from this location – which also offers safe consumption materials as well as therapeutic support from medical and social workers. Syringe vending machines and consumption rooms are both examples of harm reduction practices [1]. Yet even where such resources are available, the fact that used syringes remain to be found on the ground in public spaces is only one of many indications that they are too few and far between, to say the very least. Thus, a morning encounter with one person’s nighttime trash serves as a call for ongoing collective engagement with a widespread need that cannot just be swept aside.

[1] For the location of syringe vending machines and consumption rooms in Germany, see: https://www.spritzenautomaten.de/standorte; https://www.drogenkonsumraum.net/standorte

Syringe packaging and discarded mask2020

Syringe packaging and discarded mask left on a table in an urban community garden

anonymous